Barn Owl

General Description

The Barn Owl is a gray-and-tawny owl with a white, heart-shaped face and dark eyes. It has long legs. This owl is mostly white underneath, but may be buffy or spotted on its breast. The male and female look similar, but the female tends to be more densely spotted or darker below. The female is slightly larger than the male, generally with a rounder face.

Habitat

Barn Owls occur worldwide, and are usually found in open or semi-open habitats. In Washington, they are closely associated with agricultural areas or basalt cliffs, as well as forest openings, wetlands, and other relatively large, open spaces. In winter, they roost in dense conifers or barns.

Behavior

Barn Owls bob their heads and weave back and forth, giving them a spooky appearance. They hunt mostly at night, flying low over open ground, listening and watching for prey. Their vision is adapted for low light levels, and their hearing is highly precise. Barn Owls can accurately locate prey entirely by sound and strike successfully in total darkness. No other animal tested has as great an ability to locate prey by sound.

Diet

Small mammals (mostly rodents) are the main prey. When voles are abundant, they become a major source of food, and in these years, some Barn Owls may be able to raise additional broods.

Nesting

The male attracts a female with a display flight, and brings food to the female during courtship, which begins in winter. They form a long-term pair bond (that often lasts as long as both members are alive), and nesting begins early in the year, with most egg-laying between March and May. Nests are located on cliffs, in haystacks, hollow trees, burrows in irrigation canals, or in barns, old buildings, or other cavities. Barn Owls use barns and buildings less often in eastern Washington than in other parts of their range, as many of these nesting sites have been taken over by Great Horned Owls. They do not build a true nest, but much of the debris around the nest, including pellets, is formed into a depression. The female lays 2-11 eggs (usually about 5), and incubates them for 29-34 days. She begins to incubate as soon as the first egg is laid, so the young hatch 2-3 days apart. The male brings her food while she incubates. In the first two weeks after the young hatch, the female stays on the nest to brood them, and the male brings food for the female and the owlets. He delivers the food to the female, and she feeds the young. After about two weeks, the female begins to leave the young and hunt as well. The young first start to fly at about 60 days, although they return to the nest site at night for a few more weeks. Barn Owls generally raise one or two broods per year, but when food is abundant, they may raise three.

Migration Status

Barn Owls are considered resident, but some young birds wander great distances. Migratory movements have been recorded in both juvenile and adult birds.

Conservation Status

There is general concern that this widespread species is declining, but owls are difficult to survey for population trends. They seem to be expanding their range in the lower Columbia Basin. They do not appear to do well in harsh winters, and die-offs are often observed in severe winters, which may limit their numbers in some parts of Washington. As human populations continue to expand, more and more habitat is destroyed, although Barn Owls do respond well to nest-box programs. In recent years, farmers have begun to recognize their value for pest control (a family of Barn Owls can kill about 1,300 rats a year) and have provided nesting sites, which may help in the face of habitat destruction. Roadside collisions are a major cause of mortality and may threaten population levels in some areas.

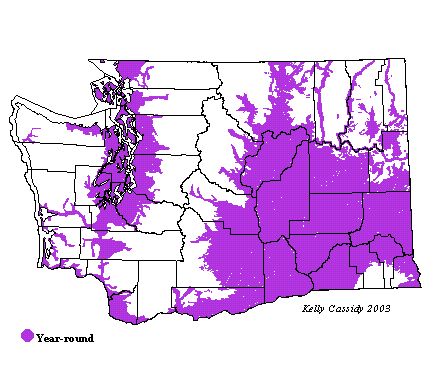

When and Where to Find in Washington

Barn Owls are fairly common permanent residents in the lowlands of eastern and western Washington. They are found on the coast in Pacific and Grays Harbor Counties, but if found farther north on the Olympic Peninsula, they are rare. They are also found in open areas on the north side of the Olympic Peninsula, near Sequim.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U |

| Puget Trough | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U |

| North Cascades | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R |

| West Cascades | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U |

| East Cascades | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U |

| Okanogan | ||||||||||||

| Canadian Rockies | ||||||||||||

| Blue Mountains | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R |

| Columbia Plateau | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map