Western Sandpiper

General Description

The most abundant shorebird in Washington, the Western Sandpiper is a member of the group known as peeps or stints. In breeding plumage, it has a deep rufous crown and cheek patch, and rufous on the wings. It is heavily streaked and spotted on the breast and back. By fall, much of this color has faded or worn off. Its slightly drooping bill, black legs, and bright rufous patches in breeding plumage help distinguish it from the other Washington peeps, the Least and Semipalmated Sandpipers. The adult in non-breeding plumage is drab gray with a white breast. Juveniles look similar to adults in breeding plumage, but their breasts are not streaked. They have rufous on their backs, but not on their heads or cheeks. Their plumage is not sexually dimorphic, but females have slightly longer bills than males. In flight, they show a white stripe down their wings and white on either side of their tails.

Habitat

Most of the population of Western Sandpipers breeds in Alaska, in dry tundra areas with low shrub cover and nearby marshes. During migration, they are mostly coastal, but some migrate across land and stop over at inland wetlands. During coastal migration and in winter, they occur in most shoreline habitats, but prefer mudflats and sandy beaches.

Behavior

Western Sandpipers form huge flocks in the spring. Typically found walking with their heads in the water, Western Sandpipers mostly probe for food, but will also pick food from the surface. Because of their long bills, they can feed in deeper water than other peeps.

Diet

During the breeding season, insect larvae are the food of choice. The migration and winter diet is primarily crustaceans, mollusks, marine worms, and other aquatic invertebrates.

Nesting

Males typically arrive on the breeding grounds first and establish territories. Monogamous pair bonds form after the females arrive. The male starts several nest scrapes, and the female selects one and lines it with leaves, lichen, and sedge. Both parents incubate the four eggs for 21 days. The young leave the nest within a few hours of hatching and find their own food. The female often deserts the group within a few days of hatching, and joins other post-breeding females in a flock. The male tends the young, and broods them in cold weather until they can fly, at 17 to 21 days.

Migration Status

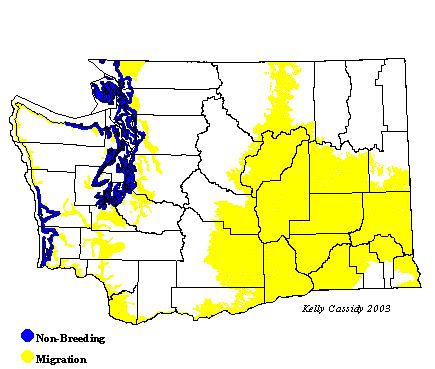

Most Western Sandpipers migrate along the Pacific Coast, but many migrate across the continent to winter on the East and Gulf Coasts. Some birds winter as far away as northern South America. Fall migration is early but prolonged. Adults begin heading south at the end of June, and juveniles follow in early August. Migration continues into fall.

Conservation Status

The Canadian Wildlife Service estimates the population at 3,500,000 birds, but other estimates are of 6,500,000 birds. Although Western Sandpipers are abundant, they are vulnerable because such a large percentage of the population gathers in so few spots during migration. Development, human disturbance, and oil spills near these stopover sites could dramatically affect the population. The Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network identifies Grays Harbor (Grays Harbor County) as a stop-over site of 'hemispheric significance.' Much of the information on population trends for Western Sandpipers in Washington is difficult to interpret due to suspected mis-identification of birds resulting in earlier counts being artificially high. Thus, some negative trends in population may be a reflection of more accurate current counts, rather than a true decline, although this should not diminish the importance of habitat protection.

When and Where to Find in Washington

Western Sandpipers may be found year round along Washington's coast, although they are most common during migration. They are rare from late May to late June, when fall migrants start to arrive. They become common in July, and remain common through mid-May, when they start tapering off as they head to northern breeding grounds. Juveniles are very widespread in the fall, often occurring in a wider range of habitats, including southern Puget Sound. Wintering birds are usually found at Grays Harbor (Grays Harbor County), Willapa Bay (Pacific County), and Drayton Harbor (Whatcom County). Most of these are first-year males. Grays Harbor hosts hundreds of thousands of migrating Western Sandpipers in April. Eastern Washington also sees migrating Western Sandpipers, although they are far more common in the fall than in the spring. They are uncommon from mid-April to late May in the spring, and common from July through September in the fall. Birds are also seen on either end of these ranges, although they are rare.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | U | U | U | C | C | U | F | C | C | F | U | U |

| Puget Trough | U | U | U | C | C | R | C | C | C | F | U | U |

| North Cascades | R | R | U | |||||||||

| West Cascades | R | F | U | F | F | F | U | R | ||||

| East Cascades | R | U | U | R | ||||||||

| Okanogan | R | R | U | |||||||||

| Canadian Rockies | U | F | F | U | ||||||||

| Blue Mountains | ||||||||||||

| Columbia Plateau | F | F | C | C | C | U |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

Spotted SandpiperActitis macularius

Spotted SandpiperActitis macularius Solitary SandpiperTringa solitaria

Solitary SandpiperTringa solitaria Gray-tailed TattlerTringa brevipes

Gray-tailed TattlerTringa brevipes Wandering TattlerTringa incana

Wandering TattlerTringa incana Greater YellowlegsTringa melanoleuca

Greater YellowlegsTringa melanoleuca WilletTringa semipalmata

WilletTringa semipalmata Lesser YellowlegsTringa flavipes

Lesser YellowlegsTringa flavipes Upland SandpiperBartramia longicauda

Upland SandpiperBartramia longicauda Little CurlewNumenius minutus

Little CurlewNumenius minutus WhimbrelNumenius phaeopus

WhimbrelNumenius phaeopus Bristle-thighed CurlewNumenius tahitiensis

Bristle-thighed CurlewNumenius tahitiensis Long-billed CurlewNumenius americanus

Long-billed CurlewNumenius americanus Hudsonian GodwitLimosa haemastica

Hudsonian GodwitLimosa haemastica Bar-tailed GodwitLimosa lapponica

Bar-tailed GodwitLimosa lapponica Marbled GodwitLimosa fedoa

Marbled GodwitLimosa fedoa Ruddy TurnstoneArenaria interpres

Ruddy TurnstoneArenaria interpres Black TurnstoneArenaria melanocephala

Black TurnstoneArenaria melanocephala SurfbirdAphriza virgata

SurfbirdAphriza virgata Great KnotCalidris tenuirostris

Great KnotCalidris tenuirostris Red KnotCalidris canutus

Red KnotCalidris canutus SanderlingCalidris alba

SanderlingCalidris alba Semipalmated SandpiperCalidris pusilla

Semipalmated SandpiperCalidris pusilla Western SandpiperCalidris mauri

Western SandpiperCalidris mauri Red-necked StintCalidris ruficollis

Red-necked StintCalidris ruficollis Little StintCalidris minuta

Little StintCalidris minuta Temminck's StintCalidris temminckii

Temminck's StintCalidris temminckii Least SandpiperCalidris minutilla

Least SandpiperCalidris minutilla White-rumped SandpiperCalidris fuscicollis

White-rumped SandpiperCalidris fuscicollis Baird's SandpiperCalidris bairdii

Baird's SandpiperCalidris bairdii Pectoral SandpiperCalidris melanotos

Pectoral SandpiperCalidris melanotos Sharp-tailed SandpiperCalidris acuminata

Sharp-tailed SandpiperCalidris acuminata Rock SandpiperCalidris ptilocnemis

Rock SandpiperCalidris ptilocnemis DunlinCalidris alpina

DunlinCalidris alpina Curlew SandpiperCalidris ferruginea

Curlew SandpiperCalidris ferruginea Stilt SandpiperCalidris himantopus

Stilt SandpiperCalidris himantopus Buff-breasted SandpiperTryngites subruficollis

Buff-breasted SandpiperTryngites subruficollis RuffPhilomachus pugnax

RuffPhilomachus pugnax Short-billed DowitcherLimnodromus griseus

Short-billed DowitcherLimnodromus griseus Long-billed DowitcherLimnodromus scolopaceus

Long-billed DowitcherLimnodromus scolopaceus Jack SnipeLymnocryptes minimus

Jack SnipeLymnocryptes minimus Wilson's SnipeGallinago delicata

Wilson's SnipeGallinago delicata Wilson's PhalaropePhalaropus tricolor

Wilson's PhalaropePhalaropus tricolor Red-necked PhalaropePhalaropus lobatus

Red-necked PhalaropePhalaropus lobatus Red PhalaropePhalaropus fulicarius

Red PhalaropePhalaropus fulicarius