Short-tailed Albatross

General Description

With a wingspan that can reach 13 feet and weighing up to 25 pounds, the Short-tailed Albatross is the largest albatross in the north Pacific. Its beak is very large and pink, and its feet are yellow. Juveniles are solid brown for their first several years. The sub-adult has a white back and rump, black tail and wingtips, and yellow head with a dark band at the nape of the neck. In adult plumage there is no dark band. The bird does not reach full adult plumage until 12 to 20 years of age.

Habitat

Short-tailed Albatrosses nest on islands off Japan and spend most of their lives at sea.

Behavior

Short-tailed Albatrosses engage in elaborate courtship dances and tend to maintain long-term pair bonds. They are graceful in flight but clumsy on land. It is believed they can sleep while in flight, gliding on air currents and staying aloft without flapping for hours or even days at a time.

Diet

Squid is a staple of their diet, as it is with other albatrosses. They occasionally follow fishing vessels, picking up offal from the boats; historically, they followed whaling ships.

Nesting

Breeding colonies are currently limited to two Japanese Islands: Torishima and Minami-Kojima. Very long-lived birds, Short-tailed Albatrosses can live 40 to 60 years, and many do not breed until they are over ten years old. Birds return to breed on the island where they hatched, and reuse the same nest site year after year. The female lays a single egg on the ground, in a shallow scrape with no lining. Both parents help incubate the egg and stay on the nest if harassed, even allowing themselves to be picked up off the egg. The nesting season lasts from August to December, after which the birds return to sea until the next nesting season.

Migration Status

Young birds may stay at sea for as long as five years before first returning to land. After the breeding season, birds undertake extensive fall wanderings and can be found anywhere in the Pacific Ocean north of the Tropic of Cancer.

Conservation Status

At the beginning of the 20th Century, the Short-tailed Albatross was fairly common throughout the north Pacific. Remains found in excavations of Native American dwelling sites corroborate reports by early naturalists that this species was more common near shores than were other albatrosses. Their historic population is estimated at over a million birds. On their nesting islands, they were aggressively hunted for food, oil, eggs, feathers, and feet, and in one 17-year period, over 5 million were killed. By 1933, when all forms of Short-tailed Albatross hunting were banned, and the bans were finally enforced, the population was only 3-50 birds. They were considered extinct in the 1940s. In the 1950s, a few young pairs that had been at sea for a several years returned to Torishima Island and began to breed there. Since then, numbers have gradually increased, but a bird that is so late to breed and lays only one egg per year is slow to rebound. Currently there are an estimated 1200 birds worldwide, with 600 of breeding age. The largest colony is on Toroshima Island, an active volcano that could easily wipe out the population once again. There are no breeding populations in the United States, but several individuals have been seen regularly during the breeding season on Midway Atoll in the northwestern Hawaiian Islands. The small population size and limited breeding distribution have left the Short-tailed Albatross genetically vulnerable. It is listed as endangered by the United States Department of Fish and Wildlife, and is a candidate for listing by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.

When and Where to Find in Washington

The Short-tailed Albatross is an extremely rare bird off Washington's coastline. Between 1940 and 1990, there were only a few valid records of the Short-tailed Albatross on the West Coast south of Alaska, most between April and August. Since the early 1990s, sightings have increased, and a few birds are reported annually off the West Coast. As this bird continues its slow recovery, sightings may again become more common in this area, but this species has a long recovery ahead of it.

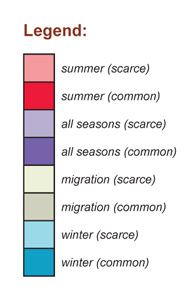

North American Range Map