Western Bluebird

General Description

The deep blue on the head, wings, and tail of the male Western Bluebird contrast with the bold rufous coloring on its breast and between its shoulders. The female is a faded version of the male and has a white eye-ring that the male lacks.

Habitat

Western Bluebirds are found in open coniferous forests, farmlands, and steppe habitats, often eastern Washington at the edges where the forest meets the steppe zone. Forest openings and clearings and agricultural areas are also good habitat for the Western Bluebird. In winter, they inhabit a wider variety of open and semi-open terrain, especially piņon-juniper forests, farmlands, and deserts.

Behavior

Western Bluebirds are often seen perching alone on fence wires, posts, snags, or tree branches by open meadows, pouncing on the ground to catch insects. They also fly out to catch aerial prey and grab insects from twigs and leaves.

Diet

In summer, Western Bluebirds eat primarily insects. In winter, berries and small fruits become more important parts of the diet, with mistletoe, juniper, and elderberry all important food items.

Nesting

The male arrives on the breeding grounds before the female, and defends the nesting territory by singing. They are cavity-nesters, finding a natural hollow in a tree, an old woodpecker hole, a hole in a building, or a man-made nest box. Preferred nest-holes are fairly low, less than 50 feet from the ground. The female builds the nest, although the male may help. The nest is a loose cup of twigs and weeds, lined with finer plant materials. The female incubates the 4 to 6 eggs, while the male brings her food. Once the eggs hatch, she broods the young while he continues to bring food. They both feed the young, which fledge at 2 to 3 weeks, The adults then have a second brood.

Migration Status

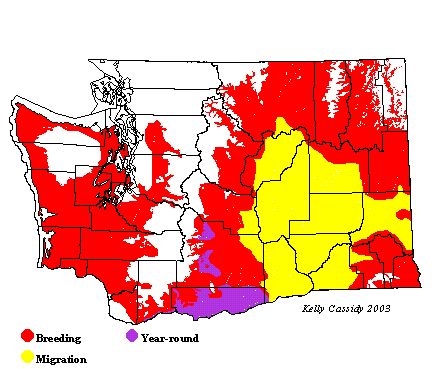

The Western Bluebird is the least migratory of the bluebirds, and much of its migration is altitudinal rather than latitudinal. In eastern Washington, most birds migrate south in the fall to locations throughout the southwestern United States and central Mexico. Small flocks occasionally remain through the winter in valleys, especially in mild winters. To the west of the Cascades, most of the population retreats to lower elevations in the winter. On both sides of the mountains, the winter range varies with food sources. In any case, they are very uncommon in winter.

Conservation Status

In recent decades, the Western Bluebird has declined over much of its range. This decline is well documented in western Washington where it is attributed to a combination of competition with House Sparrows and European Starlings for nesting cavities, a reduction of natural cavities, and regional climactic changes that have resulted in reduced numbers of prey. An intense nest box program has helped a population in the Fort Lewis area to rebound, and helped with the re-establishment of breeding pairs in other areas of western Washington where Western Bluebirds once were present.

When and Where to Find in Washington

Western Bluebirds can be found in eastern Washington at the edges where the forest meets the steppe. They are also found in open coniferous forest, especially Ponderosa pine. They are especially common in areas where nest box projects have provided them with adequate cavities. Nest boxes are in place in Kittitas, Yakima, Klickitat, Walla Walla, Columbia, and Garfield Counties. In western Washington, Western Bluebirds are now regular, but uncommon, in the Fort Lewis area, and rare in forest clearings in King, Pierce, Thurston, and Mason Counties, and in prairie areas near Port Townsend (Jefferson County), at the mouth of the Naselle River (Pacific County), Forks (Clallam County), and other sites on the eastern Olympic Peninsula. They can also be found year round in Skamania County.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R |

| Puget Trough | R | R | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | R | R | R |

| North Cascades | R | R | R | R | R | R | ||||||

| West Cascades | R | R | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | R | R | R |

| East Cascades | R | R | U | F | F | F | F | F | U | U | R | R |

| Okanogan | U | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | U | ||

| Canadian Rockies | U | U | F | F | F | F | F | F | U | |||

| Blue Mountains | R | F | F | C | C | C | C | U | R | |||

| Columbia Plateau | R | R | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | R | R |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

Northern WheatearOenanthe oenanthe

Northern WheatearOenanthe oenanthe Western BluebirdSialia mexicana

Western BluebirdSialia mexicana Mountain BluebirdSialia currucoides

Mountain BluebirdSialia currucoides Townsend's SolitaireMyadestes townsendi

Townsend's SolitaireMyadestes townsendi VeeryCatharus fuscescens

VeeryCatharus fuscescens Gray-cheeked ThrushCatharus minimus

Gray-cheeked ThrushCatharus minimus Swainson's ThrushCatharus ustulatus

Swainson's ThrushCatharus ustulatus Hermit ThrushCatharus guttatus

Hermit ThrushCatharus guttatus Dusky ThrushTurdus naumanni

Dusky ThrushTurdus naumanni RedwingTurdus iliacus

RedwingTurdus iliacus American RobinTurdus migratorius

American RobinTurdus migratorius Varied ThrushIxoreus naevius

Varied ThrushIxoreus naevius