Western Meadowlark

General Description

Western Meadowlarks look distinctively different from other members of the blackbird family in Washington. They have streaked brown upperparts and solid yellow underparts with a distinct black collar. The yellow and black are both more intense during the breeding season. They have long legs and short tails with white outer tail-feathers that are obvious in flight.

Habitat

Meadowlarks are open-country birds. They inhabit grasslands, shrub-steppe, and agricultural areas. During winter, they can often be found in cultivated fields and wet grasslands.

Behavior

Western Meadowlarks flock in winter in single-species groups, or with other blackbirds and starlings. Meadowlarks forage mostly on the ground, running or walking, and probing the soil with their bills. In early spring, Western Meadowlarks sing continually from shrub tops, fence posts, utility poles, or any other high structure in their open-country habitat.

Diet

During the summer, insects make up most of the diet. In fall and winter, seeds and waste grain become more important.

Nesting

Western Meadowlarks nest on the ground, often in small dips or hollows, such as those created by cow footprints. Nests are typically under dense vegetation and can be very difficult to find. Western Meadowlarks are polygynous. Successful males generally mate with two females at a time. Females build the nests, which are grass domes with side entrances. The nest materials are often interwoven with adjacent growth, and small trails may form through the grass to the nests. Females incubate 4 to 6 eggs for 13 to 14 days. The females brood the young after they hatch and provide most of the food, although the male may help. The young leave the nest 10 to 12 days after hatching. They cannot fly at this age but can run well, and, with the help of cryptic plumage, can hide successfully in the grass. Females often raise two broods a season.

Migration Status

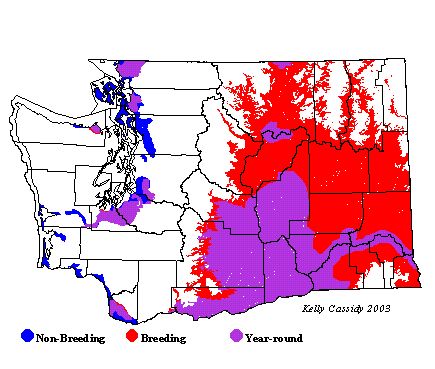

Western Meadowlarks are resident throughout much of their range, but when deep snow covers food sources they may move into sheltered valleys. Some populations appear to be long-distance migrants.

Conservation Status

Western Meadowlarks are abundant and widespread, but breeding populations have declined slightly throughout their range in recent years, a trend seen in Washington in both the winter and breeding seasons. Most of this decline can probably be attributed to habitat destruction from livestock grazing, mowing, and development, and contamination from pesticides. In northeastern Washington, the conversion of forested river valleys to agricultural uses may be increasing available habitat, but western Washington populations have declined significantly in recent years as the remaining prairie in this part of the state is developed, degraded by invasive plants, or altered by fire suppression. Western Meadowlarks are extremely sensitive to human disturbance during the breeding season and will abort nesting attempts if they are flushed while incubating eggs.

When and Where to Find in Washington

During the breeding season, Western Meadowlarks can be found in open lowlands throughout the state, but are most abundant in eastern Washington. Western Washington breeders are rare to uncommon, and are locally distributed in the Puget Trough, the Vancouver lowlands, and Sequim, where they remain year round, and are joined in winter by birds from the north and east. Most leave eastern Washington locations, although some may overwinter near feedlots in the Columbia and Snake River valleys. They start to return to the shrub-steppe zone in late February, and are common by mid-April.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | U | U | U | U | R | U | U | U | U | |||

| Puget Trough | U | U | U | U | U | R | R | R | R | U | U | U |

| North Cascades | R | R | R | R | R | |||||||

| West Cascades | R | R | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | R | R |

| East Cascades | U | U | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | U | U | U |

| Okanogan | R | R | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | R |

| Canadian Rockies | F | F | C | C | C | F | F | U | ||||

| Blue Mountains | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | ||||

| Columbia Plateau | F | F | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | F | F |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

BobolinkDolichonyx oryzivorus

BobolinkDolichonyx oryzivorus Red-winged BlackbirdAgelaius phoeniceus

Red-winged BlackbirdAgelaius phoeniceus Tricolored BlackbirdAgelaius tricolor

Tricolored BlackbirdAgelaius tricolor Western MeadowlarkSturnella neglecta

Western MeadowlarkSturnella neglecta Yellow-headed BlackbirdXanthocephalus xanthocephalus

Yellow-headed BlackbirdXanthocephalus xanthocephalus Rusty BlackbirdEuphagus carolinus

Rusty BlackbirdEuphagus carolinus Brewer's BlackbirdEuphagus cyanocephalus

Brewer's BlackbirdEuphagus cyanocephalus Common GrackleQuiscalus quiscula

Common GrackleQuiscalus quiscula Great-tailed GrackleQuiscalus mexicanus

Great-tailed GrackleQuiscalus mexicanus Brown-headed CowbirdMolothrus ater

Brown-headed CowbirdMolothrus ater Orchard OrioleIcterus spurius

Orchard OrioleIcterus spurius Hooded OrioleIcterus cucullatus

Hooded OrioleIcterus cucullatus Bullock's OrioleIcterus bullockii

Bullock's OrioleIcterus bullockii Baltimore OrioleIcterus galbula

Baltimore OrioleIcterus galbula Scott's OrioleIcterus parisorum

Scott's OrioleIcterus parisorum