White-winged Scoter

General Description

Scoters are large, mostly black or dark gray sea ducks, and the White-winged Scoter is the largest of the three species. All plumages have a white wing-patch, which distinguishes the White-winged Scoter in flight from the other two scoters, which have solid black wings. The White-winged Scoter can also be distinguished by its sloping forehead and bill, which is less bulbous than that of the others. The adult male is solid black with a white comma around a white eye. Its bill is yellow and has a dark knob at the base. The juvenile and the female have light gray patches in front of and behind their eyes, and are dark gray overall with gray bills.

Habitat

White-winged Scoters nest on freshwater lakes and wetlands in open country in the northwest interior of North America. They winter in open, coastal environments, favoring bays and inlets with sandy shores and shellfish beds. White-winged Scoters are generally found in deeper water and farther from shore than the other scoters.

Behavior

White-winged Scoters spend the non-breeding part of the year in large flocks on the ocean. They feed almost exclusively by diving, taking prey from the ocean floor, and swallowing the small items under water. Scoters are strong flyers, but must get a running start along the water to get airborne.

Diet

During winter, mollusks and crustaceans are the most common food item. During the breeding season, aquatic insect larvae become a predominant part of the diet. Crustaceans and other aquatic invertebrates are also eaten.

Nesting

White-winged Scoters probably form pair bonds during migration in their second or third year. Nests are built on the ground close to water, and hidden by brush. The nest is a shallow depression lined with down and occasionally additional plant material. The female typically lays 8 to 10 eggs and incubates them for 25 to 30 days. The pair bond dissolves, and the male leaves soon after incubation begins. Pair bonds do not appear to re-form between the same birds in succeeding years. The young leave the nest shortly after hatching and feed themselves. The female tends the young and broods them at night for 1 to 3 weeks, after which she leaves them to fend for themselves. They fledge at 63 to 77 days.

Migration Status

White-winged Scoters are among the latest migrant ducks to reach the breeding grounds, and much is not known about their migratory patterns. Males appear to winter farther north than females, and molting sites are in unknown, remote locations.

Conservation Status

White-winged Scoters were formerly more numerous, breeding in prairie habitats where they no longer breed. Changes in land use associated with agriculture in these regions have left the scoters without cover for nesting. There are other challenges, too. Of all seabirds, scoters are among the most vulnerable to oil spills. Blue mussels, one of their staple prey species, are known to concentrate toxic chemicals, potentially passing this toxicity on to White-winged Scoters. The scoters' strong fidelity to breeding sites, low productivity, and slow maturation make them slow to rebound from losses and make those losses of greater concern.

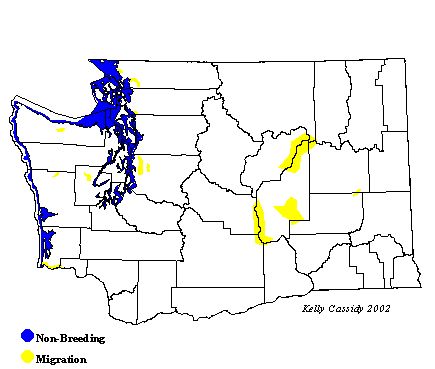

When and Where to Find in Washington

White-winged Scoters vary from uncommon to abundant along Washington's coastline and in Puget Sound from the late summer through spring (July through mid-June). Areas of abundance vary from year to year. White-winged Scoters are the most common scoter to be found on inland sites outside of the breeding season. Throughout Washington's lowlands, while still rare, White-winged Scoters may be seen on lakes and wetlands in late fall or early winter during migration. Flocks of non-breeders can also be seen in coastal areas in summer in some of the more heavily used winter locations such as Penn Cove off Whidbey Island and Drayton Harbor (Whatcom County).

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | C | C | C | C | C | U | U | F | C | C | C | C |

| Puget Trough | C | C | C | C | C | F | U | U | F | F | C | C |

| North Cascades | ||||||||||||

| West Cascades | ||||||||||||

| East Cascades | R | R | ||||||||||

| Okanogan | R | |||||||||||

| Canadian Rockies | ||||||||||||

| Blue Mountains | ||||||||||||

| Columbia Plateau | R | R |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

Fulvous Whistling-DuckDendrocygna bicolor

Fulvous Whistling-DuckDendrocygna bicolor Taiga Bean-GooseAnser fabalis

Taiga Bean-GooseAnser fabalis Greater White-fronted GooseAnser albifrons

Greater White-fronted GooseAnser albifrons Emperor GooseChen canagica

Emperor GooseChen canagica Snow GooseChen caerulescens

Snow GooseChen caerulescens Ross's GooseChen rossii

Ross's GooseChen rossii BrantBranta bernicla

BrantBranta bernicla Cackling GooseBranta hutchinsii

Cackling GooseBranta hutchinsii Canada GooseBranta canadensis

Canada GooseBranta canadensis Mute SwanCygnus olor

Mute SwanCygnus olor Trumpeter SwanCygnus buccinator

Trumpeter SwanCygnus buccinator Tundra SwanCygnus columbianus

Tundra SwanCygnus columbianus Wood DuckAix sponsa

Wood DuckAix sponsa GadwallAnas strepera

GadwallAnas strepera Falcated DuckAnas falcata

Falcated DuckAnas falcata Eurasian WigeonAnas penelope

Eurasian WigeonAnas penelope American WigeonAnas americana

American WigeonAnas americana American Black DuckAnas rubripes

American Black DuckAnas rubripes MallardAnas platyrhynchos

MallardAnas platyrhynchos Blue-winged TealAnas discors

Blue-winged TealAnas discors Cinnamon TealAnas cyanoptera

Cinnamon TealAnas cyanoptera Northern ShovelerAnas clypeata

Northern ShovelerAnas clypeata Northern PintailAnas acuta

Northern PintailAnas acuta GarganeyAnas querquedula

GarganeyAnas querquedula Baikal TealAnas formosa

Baikal TealAnas formosa Green-winged TealAnas crecca

Green-winged TealAnas crecca CanvasbackAythya valisineria

CanvasbackAythya valisineria RedheadAythya americana

RedheadAythya americana Ring-necked DuckAythya collaris

Ring-necked DuckAythya collaris Tufted DuckAythya fuligula

Tufted DuckAythya fuligula Greater ScaupAythya marila

Greater ScaupAythya marila Lesser ScaupAythya affinis

Lesser ScaupAythya affinis Steller's EiderPolysticta stelleri

Steller's EiderPolysticta stelleri King EiderSomateria spectabilis

King EiderSomateria spectabilis Common EiderSomateria mollissima

Common EiderSomateria mollissima Harlequin DuckHistrionicus histrionicus

Harlequin DuckHistrionicus histrionicus Surf ScoterMelanitta perspicillata

Surf ScoterMelanitta perspicillata White-winged ScoterMelanitta fusca

White-winged ScoterMelanitta fusca Black ScoterMelanitta nigra

Black ScoterMelanitta nigra Long-tailed DuckClangula hyemalis

Long-tailed DuckClangula hyemalis BuffleheadBucephala albeola

BuffleheadBucephala albeola Common GoldeneyeBucephala clangula

Common GoldeneyeBucephala clangula Barrow's GoldeneyeBucephala islandica

Barrow's GoldeneyeBucephala islandica SmewMergellus albellus

SmewMergellus albellus Hooded MerganserLophodytes cucullatus

Hooded MerganserLophodytes cucullatus Common MerganserMergus merganser

Common MerganserMergus merganser Red-breasted MerganserMergus serrator

Red-breasted MerganserMergus serrator Ruddy DuckOxyura jamaicensis

Ruddy DuckOxyura jamaicensis