Harlequin Duck

General Description

The distinctive Harlequin Duck is a small sea duck with a small bill, short neck, and long tail. Males in breeding plumage are unmistakable with their dark blue color, rufous sides and crown, and striking white patterning on the face, neck, sides, and back. In non-breeding plumage the males are brown with white on the face and a round white spot at each ear. A subtle white shoulder stripe and white on the wings distinguishes the male in non-breeding plumage from the juvenile and the female, which look similar.

Habitat

Harlequin Ducks prefer turbulent water, both in their breeding habitat, which is along fast-moving mountain streams, and in their wintering habitat, which is along rocky coastlines. The mountain streams are usually at low to subalpine elevations within a closed forest canopy, and have midstream gravel bars or rocks for roosting. Coastal habitat is typically in the shallow, intertidal zones along rocky coastlines, where rough surf is the norm.

Behavior

Harlequin Ducks are well adapted to their harsh surroundings. They make their way against the current and easily climb up steep and slippery rocks, although many have been found with broken bones, presumably from being dashed against rocks in the rough surf. Like other diving ducks they forage under water, although in addition to diving they also walk along the bottom or dabble. When they find food at the bottom, they pry it open with their bills.

Diet

In coastal habitat, mollusks and crustaceans make up the bulk of the diet. Some small fish and marine worms are also eaten. On rivers, aquatic insects are the main prey, especially larvae attached to rocks on the river bottom.

Nesting

Most females first breed at the age of two, and males at the age of three, although breeding success for many birds remains low until they are five years old. Pairs form during winter and spring, and dissolve after the female begins incubation. At this time, the male leaves the female and the breeding territory. They reunite in the fall on the wintering grounds. The well-concealed nest is located close to a stream, on the ground, on a small cliff ledge, in a tree cavity, or in a stump. It is a shallow depression lined with vegetation and down. The female lays 5 to 7 eggs and incubates them for 27 to 30 days. The chicks leave the nest shortly after hatching, remain near the nesting area for a few weeks, and then move downstream. The female tends the young and leads them to feeding areas, and the young feed themselves. They can dive at a very young age, but find most of their food on the surface at first. It is not unusual to see combined broods tended by more than one female. The young can fly at about 5 to 6 weeks.

Migration Status

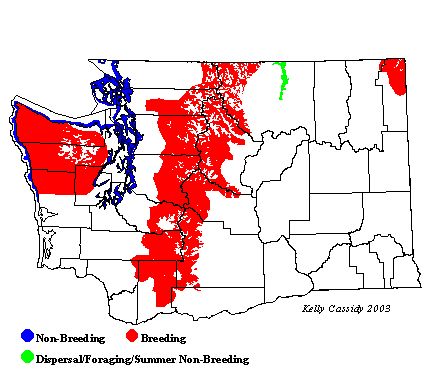

Short-distance migrants, Harlequin Ducks move from the coast inland and back again. When they migrate inland, they usually fly low, following the course of a river. Males leave the breeding area for molting areas in the Strait of Juan de Fuca and Puget Sound in late June or early July. Females and the young of the year leave the breeding grounds in August. Harlequin Duck migration often does not take the standard north-south pattern found in many birds; Harlequins wintering on the Pacific Coast and in Puget Sound may move south or west (to the Olympic Peninsula) to breed.

Conservation Status

While the population of Harlequin Ducks in the Pacific Northwest appears to be stable, much research is currently under way to get a better sense of how the species is faring. Harlequin Ducks are listed as a priority species by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. They are subject to many potential threats, including shoreline development, hunting, and fishing nets. Oil spills are also a potential threat, and as recently as 1998, Alaskan Harlequin Ducks were still exhibiting reduced survival rates as a result of the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill. In Washington, however, logging is probably the most significant threat. Logging activities remove suitable forests along streams and also can add silt and sediment to the streams, reducing the amount of prey. Because Harlequin Ducks take a number of years to reach maturity, they are slower to rebound from threats, and great care must be taken to prevent a negative impact on the population.

When and Where to Find in Washington

As a breeder, the Harlequin Duck is uncommon below 4,000 feet in the Cascade, Olympic, and Selkirk Mountains from mid-March through mid-August. They are rare in the Blue Mountains and southern Cascades. In winter they are common in saltwater habitat along rocky shorelines and jetties, more common in Puget Sound north of Seattle than south. They are most common along the outer coast of Whidbey Island. Another wintering site is at Rosario Beach at Deception Pass State Park on Fidalgo Island (Skagit County). They are also regularly seen at Birch Bay and Semiahmoo Spit (Whatcom County). In summer, they can sometimes be seen along the gravel bars of the Methow River south of Winthrop (Okanogan County).

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | F | F | F | U | U | U | U | U | F | F | F | F |

| Puget Trough | F | F | F | U | U | U | F | F | F | F | F | F |

| North Cascades | R | U | U | U | U | R | ||||||

| West Cascades | R | U | U | U | U | U | R | R | ||||

| East Cascades | U | U | U | U | ||||||||

| Okanogan | U | U | U | R | ||||||||

| Canadian Rockies | U | U | U | U | U | |||||||

| Blue Mountains | ||||||||||||

| Columbia Plateau |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

Fulvous Whistling-DuckDendrocygna bicolor

Fulvous Whistling-DuckDendrocygna bicolor Taiga Bean-GooseAnser fabalis

Taiga Bean-GooseAnser fabalis Greater White-fronted GooseAnser albifrons

Greater White-fronted GooseAnser albifrons Emperor GooseChen canagica

Emperor GooseChen canagica Snow GooseChen caerulescens

Snow GooseChen caerulescens Ross's GooseChen rossii

Ross's GooseChen rossii BrantBranta bernicla

BrantBranta bernicla Cackling GooseBranta hutchinsii

Cackling GooseBranta hutchinsii Canada GooseBranta canadensis

Canada GooseBranta canadensis Mute SwanCygnus olor

Mute SwanCygnus olor Trumpeter SwanCygnus buccinator

Trumpeter SwanCygnus buccinator Tundra SwanCygnus columbianus

Tundra SwanCygnus columbianus Wood DuckAix sponsa

Wood DuckAix sponsa GadwallAnas strepera

GadwallAnas strepera Falcated DuckAnas falcata

Falcated DuckAnas falcata Eurasian WigeonAnas penelope

Eurasian WigeonAnas penelope American WigeonAnas americana

American WigeonAnas americana American Black DuckAnas rubripes

American Black DuckAnas rubripes MallardAnas platyrhynchos

MallardAnas platyrhynchos Blue-winged TealAnas discors

Blue-winged TealAnas discors Cinnamon TealAnas cyanoptera

Cinnamon TealAnas cyanoptera Northern ShovelerAnas clypeata

Northern ShovelerAnas clypeata Northern PintailAnas acuta

Northern PintailAnas acuta GarganeyAnas querquedula

GarganeyAnas querquedula Baikal TealAnas formosa

Baikal TealAnas formosa Green-winged TealAnas crecca

Green-winged TealAnas crecca CanvasbackAythya valisineria

CanvasbackAythya valisineria RedheadAythya americana

RedheadAythya americana Ring-necked DuckAythya collaris

Ring-necked DuckAythya collaris Tufted DuckAythya fuligula

Tufted DuckAythya fuligula Greater ScaupAythya marila

Greater ScaupAythya marila Lesser ScaupAythya affinis

Lesser ScaupAythya affinis Steller's EiderPolysticta stelleri

Steller's EiderPolysticta stelleri King EiderSomateria spectabilis

King EiderSomateria spectabilis Common EiderSomateria mollissima

Common EiderSomateria mollissima Harlequin DuckHistrionicus histrionicus

Harlequin DuckHistrionicus histrionicus Surf ScoterMelanitta perspicillata

Surf ScoterMelanitta perspicillata White-winged ScoterMelanitta fusca

White-winged ScoterMelanitta fusca Black ScoterMelanitta nigra

Black ScoterMelanitta nigra Long-tailed DuckClangula hyemalis

Long-tailed DuckClangula hyemalis BuffleheadBucephala albeola

BuffleheadBucephala albeola Common GoldeneyeBucephala clangula

Common GoldeneyeBucephala clangula Barrow's GoldeneyeBucephala islandica

Barrow's GoldeneyeBucephala islandica SmewMergellus albellus

SmewMergellus albellus Hooded MerganserLophodytes cucullatus

Hooded MerganserLophodytes cucullatus Common MerganserMergus merganser

Common MerganserMergus merganser Red-breasted MerganserMergus serrator

Red-breasted MerganserMergus serrator Ruddy DuckOxyura jamaicensis

Ruddy DuckOxyura jamaicensis