Northern Pintail

General Description

Slim and long-necked, Northern Pintails have an elegant appearance on water and in flight. The male in breeding plumage has a dark brown head, white breast and throat, and a white line extending up the neck. The body is light gray with black-edged feathers, and the belly is white. The rump and the long tail are black. The female is mottled brown-and-black with a pointed tail and dark bronze speculum on its wing. Both sexes have gray legs and a dark gray bill, although the bill of the male is lined with blue on the sides. Males in eclipse plumage are similar to females, but are grayer, with some white remaining on the sides of the neck.

Habitat

During the breeding season, Northern Pintails use shallow ponds and marshes in open areas. In winter they can be found around shallow wetlands, exposed mudflats, flooded fields, or lakes. During migration, they have been seen in offshore waters.

Behavior

Northern Pintails are wary, especially during their flightless stage in late summer, when they are highly secretive. They will forage on land, but find most of their food by dabbling in shallow, muddy water.

Diet

In fall and winter, Northern Pintails eat seeds and waste grain. In spring and summer, roots and new shoots as well as aquatic invertebrates make up the majority of the diet. As with many other species of duck, the young eat a greater proportion of invertebrates than the adults.

Nesting

Pairing begins on the wintering grounds and continues through spring migration. Northern Pintails are among the earliest nesters, and arrive on the breeding grounds as soon as they are free of ice. The nest is located on dry ground in short vegetation. It is usually near water, but may be up to half a mile away from the nearest body of water. Pintail nests are often more exposed than other ducks' nests. The nest is a shallow depression, built by the female and made of grass, twigs, or leaves, lined with down. Incubation of the 6 to 10 eggs lasts from 21 to 25 days and is done by the female alone. The pair bond dissolves shortly after the female begins incubation, when the males gather in flocks to molt. Within a few hours of hatching, the young follow the female from the nest site. They can feed themselves, but the female continues to tend them until they fledge at 38 to 52 days. In the far north where continuous daylight allows for round-the-clock feeding, the young develop faster.

Migration Status

Northern Pintails are early-fall migrants and begin to arrive on their wintering grounds starting in August, although the peak of the fall migration is in October in eastern Washington and November in western Washington. The northward migration begins early in the spring, from late February to mid-May, peaking in March and early April. Many Pintail flocks migrate from Siberia across the Bering Strait to winter in North America.

Conservation Status

Widespread and common throughout North America, Europe, and Asia, the Northern Pintail is probably one of the most numerous species of duck worldwide. Numbers in North America vary a great deal from year to year, although some surveys have recorded significant, long-term declines since the 1960s. Predators and farming operations destroy many thousands of Northern Pintail nests each year. Farming has also affected nesting habitat. Pintails appear to be responding to new conservation practices, however, including habitat restoration and tighter restrictions on hunting, and numbers seem to be increasing. If these practices are maintained, Northern Pintails should be able to maintain a healthy population in North America.

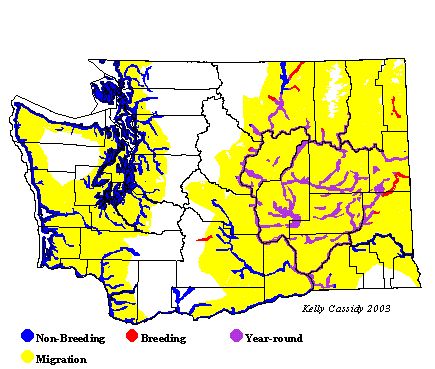

When and Where to Find in Washington

Northern Pintails are uncommon breeders in freshwater ponds and wetlands in the central Columbia Basin. The majority of Pintails breeding in Washington can be found in southern Grant and Adams Counties. In western Washington, some birds breed in less-developed parts of the southern Puget Trough, but summer sightings are most often non-breeders. During migration and winter, Northern Pintails are very common birds on the coast and in Puget Sound. They are most common in western Washington from late August to early May. In eastern Washington, they may be found all year.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | C | C | C | C | C | R | R | U | C | C | C | C |

| Puget Trough | C | C | C | C | U | R | R | U | C | C | C | C |

| North Cascades | U | U | U | F | R | U | U | U | U | |||

| West Cascades | C | C | C | C | F | R | R | R | F | C | C | C |

| East Cascades | R | R | U | U | U | R | R | U | U | R | ||

| Okanogan | U | C | C | U | U | U | U | U | C | C | ||

| Canadian Rockies | F | C | C | F | U | U | U | F | F | U | ||

| Blue Mountains | R | R | R | R | ||||||||

| Columbia Plateau | C | C | C | C | U | U | U | U | F | C | C | C |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

Fulvous Whistling-DuckDendrocygna bicolor

Fulvous Whistling-DuckDendrocygna bicolor Taiga Bean-GooseAnser fabalis

Taiga Bean-GooseAnser fabalis Greater White-fronted GooseAnser albifrons

Greater White-fronted GooseAnser albifrons Emperor GooseChen canagica

Emperor GooseChen canagica Snow GooseChen caerulescens

Snow GooseChen caerulescens Ross's GooseChen rossii

Ross's GooseChen rossii BrantBranta bernicla

BrantBranta bernicla Cackling GooseBranta hutchinsii

Cackling GooseBranta hutchinsii Canada GooseBranta canadensis

Canada GooseBranta canadensis Mute SwanCygnus olor

Mute SwanCygnus olor Trumpeter SwanCygnus buccinator

Trumpeter SwanCygnus buccinator Tundra SwanCygnus columbianus

Tundra SwanCygnus columbianus Wood DuckAix sponsa

Wood DuckAix sponsa GadwallAnas strepera

GadwallAnas strepera Falcated DuckAnas falcata

Falcated DuckAnas falcata Eurasian WigeonAnas penelope

Eurasian WigeonAnas penelope American WigeonAnas americana

American WigeonAnas americana American Black DuckAnas rubripes

American Black DuckAnas rubripes MallardAnas platyrhynchos

MallardAnas platyrhynchos Blue-winged TealAnas discors

Blue-winged TealAnas discors Cinnamon TealAnas cyanoptera

Cinnamon TealAnas cyanoptera Northern ShovelerAnas clypeata

Northern ShovelerAnas clypeata Northern PintailAnas acuta

Northern PintailAnas acuta GarganeyAnas querquedula

GarganeyAnas querquedula Baikal TealAnas formosa

Baikal TealAnas formosa Green-winged TealAnas crecca

Green-winged TealAnas crecca CanvasbackAythya valisineria

CanvasbackAythya valisineria RedheadAythya americana

RedheadAythya americana Ring-necked DuckAythya collaris

Ring-necked DuckAythya collaris Tufted DuckAythya fuligula

Tufted DuckAythya fuligula Greater ScaupAythya marila

Greater ScaupAythya marila Lesser ScaupAythya affinis

Lesser ScaupAythya affinis Steller's EiderPolysticta stelleri

Steller's EiderPolysticta stelleri King EiderSomateria spectabilis

King EiderSomateria spectabilis Common EiderSomateria mollissima

Common EiderSomateria mollissima Harlequin DuckHistrionicus histrionicus

Harlequin DuckHistrionicus histrionicus Surf ScoterMelanitta perspicillata

Surf ScoterMelanitta perspicillata White-winged ScoterMelanitta fusca

White-winged ScoterMelanitta fusca Black ScoterMelanitta nigra

Black ScoterMelanitta nigra Long-tailed DuckClangula hyemalis

Long-tailed DuckClangula hyemalis BuffleheadBucephala albeola

BuffleheadBucephala albeola Common GoldeneyeBucephala clangula

Common GoldeneyeBucephala clangula Barrow's GoldeneyeBucephala islandica

Barrow's GoldeneyeBucephala islandica SmewMergellus albellus

SmewMergellus albellus Hooded MerganserLophodytes cucullatus

Hooded MerganserLophodytes cucullatus Common MerganserMergus merganser

Common MerganserMergus merganser Red-breasted MerganserMergus serrator

Red-breasted MerganserMergus serrator Ruddy DuckOxyura jamaicensis

Ruddy DuckOxyura jamaicensis