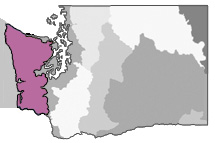

Pacific Northwest Coast Ecoregion and Birding Sites

Click to see a detailed map with birding sites. |

Location

This ecoregion includes most of the Olympic Peninsula (but not its northern and eastern coastal plain), the lowlands of the Chehalis River drainage and around Grays Harbor and Willapa Bay, the Willapa Hills, and coastal waters out to three miles offshore on the outer coast and out to the international boundary on the Strait of Juan de Fuca west of the mouth of the Twin Rivers. It is bordered on the east by the Puget Trough lowlands, and on the south by the Columbia River. The ecoregion itself extends north to Vancouver Island and south through much of the Coast Ranges of Oregon.

Physiography

Elevated areas vary from the highly dissected peaks and valleys of the Olympics, pushed up well above 7,500 feet by colliding tectonic plates, to the much lower, rounded, and more recent Willapa Hills, also uplifted from volcanic activity in the sea-a process that continues today. Extensive coastal lowlands with sedimentary marine and glacial deposits border both sets of uplands and are more extensive in the Chehalis River basin. Grays Harbor and Willapa Bay are two of the most important estuaries on the Pacific Coast. Pleistocene glaciation carved valleys and cirques in the Olympics and extended south to the Chehalis River. The coast north of Grays Harbor is rugged, with cliffs and jagged islands, while from Grays Harbor south flatness and sand dunes prevail. The Lower Columbia River is a prominent landscape feature important for birds.

Climate

Cold, wet winters and cool, moist summers characterize the ecoregion, and the west side of the Olympics is the wettest part of the state, large areas receiving more than 150 inches of rain in an average year, locally over 200 inches. Coastal lowlands receive much less precipitation (e.g., 84 inches at Aberdeen) but are still very wet. Snow blankets the Olympics with accumulations up to 10 feet or more and persists at higher elevations into mid-summer (although only episodic in the lowland winters), and the higher peaks have permanent glaciers. The southern end of the ecoregion is distinctly warmer than the northern end, spring arriving perceptibly earlier. With prevailing southwesterly winds dropping most of their moisture on west slopes, the northeastern corner of the region is in a distinct rain shadow, the annual precipitation declining dramatically toward the coastal lowlands.

Habitats

The original vegetation was heavy conifer forest from coast to treeline, dominated in the lowlands by western hemlock, western red cedar, and Douglas-fir, with Sitka spruce locally dominant on the coast and up lowland river valleys. Common broadleaf trees, again mostly associated with river valleys, are red alder, black cottonwood, and bigleaf maple. Vine maple and other small trees and numerous evergreen shrubs, especially in the heather family, are common in the forest understory. The wettest west-side forests have been rightfully called temperate rain forests. Higher elevations feature smaller trees of different species, for example Pacific silver fir, subalpine fir, mountain hemlock, and Alaska yellow cedar, and highest elevations have ever-diminishing tree height and subalpine meadows until open alpine parkland gives way to snow and ice. On the drier east side of the Olympics, a drier, more open conifer forest occurs but with mostly the same species. Coastal dunes and salt marshes support large stands of herbaceous vegetation containing strictly coastal plant species. Freshwater wetlands consist largely of stream and river systems draining the uplands all along the coast, but there are marshes, ponds, and lakes scattered around the flat lowlands and numerous alpine lakes in the Olympic Mountains. Sphagnum bogs are of local significance. Coastal waters are underlain by rock and sand, depending on coastal topography, and support dense communities of marine algae and invertebrates. Because of ongoing logging, stands in all stages of forest succession are scattered through most of the ecoregion.

Human Impact

Elevated areas are lightly settled by humans, river valleys much more so, but only parts of Grays Harbor and the sand dunes of the southern coast have been substantially affected by development. Agriculture has a minor impact, but logging, which has occurred over a very large proportion of the ecoregion, has had a major effect on the original vegetation cover. The major stronghold of old-growth forest is Olympic National Park, covering much of the center of the Olympic Peninsula, but the majority of old growth in the ecoregion has been logged at least once. Commercial fishing, as well as dams up the Columbia River, have had an impact on fish faunas, which in turn affect seabirds.

Bird

Checklist

Bird

Checklist